|

|||||||||

|

Welcome to the Autumn 2014 Newsletter from the Kent Archaeological Field School

Zoe and Sue uncovered a large apse at the north-east end of the Roman building at Abbey Fields in Faversham. The building started life as an aisled barn but was transformed into an extremely large bath-house which was still standing in the early 5th century. Adjacent to the apse- which we will explore more fully next year Louise (below) found a rather primitive, but effective hypocaust system and spent her last day on site excavating a range of potential Roman toilets.

year the KAFS Christmas Party will be held at the Field School in Faversham on a Saturday in late December- see www.kafs.co.uk for details! OPLONTIS - The Villas ‘A’ and ‘B’

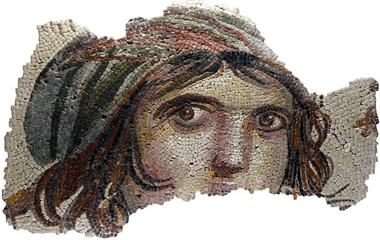

The Oplontis Project began in 2006 with the study of the site known as Oplontis situated at Torre Annunziata, Italy. The work is sponsored by the Center for the Study of Ancient Italy at the University of Texas in Austin. Its two directors are John R. Clarke and Michael L. Thomas. In addition the Kent Archaeological Field School, Faversham, Kent UK under its director Paul Wilkinson has been involved in fieldwork at both villa sites since 2008.  The aims of the project are to enable an understanding of the two buildings, one of which is Villa ‘A’, the other Villa ‘B’ to be enhanced through a comprehensive study of the buildings, the fabric, the artefacts and human remains, their location, and their function including a 3-d model with interactive database which will enable scholars to write a series of comprehensive volumes which will be published by the Humanities eBook series of the American Council of Learned Societies. The first is scheduled to appear in 2014. Villa ‘A’ is now recognised as one of the most sumptuous and extravagant Roman villas overlooking the Bay of Naples. It is thought by many that the villa was the property of Poppaea Sabina the Younger who was born in Pompeii in AD30 and married Nero in AD62. The evidence is somewhat circumstantial and consists of graffiti found on an amphora which said ‘secundo poppaea’ which in translation means ‘to the second [slave or freedman] of Poppaea’. The villa was excavated by an Italian team over twenty years ago, and although it was impossible because of modern development to find the limits of the villa some 99 rooms and spaces were excavated including a sixty metre swimming pool and formal gardens.  The villa is probably best known for its wonderful Second Style wall frescoes which can be found in a number of rooms located around the atrium, itself dating back to about 50BC. Villa ‘B’ is located about 300 metres to the east of Villa ‘A’ and is not a villa. Its likely function was a warehouse where wine would be processed and shipped out in amphorae. Some 400 amphorae still litter the site. Around the warehouse are roads and streets of town houses still waiting to be excavated. The plan of the warehouse is focused on a central courtyard surrounded by a two-storey peristyle of Nocera tufa columns. The eastern side of the peristyle includes an entrance opening onto an unexcavated road running north south and detected through our coring campaign. Ground floor storage rooms open up into this central space whilst above on the second floor are residential rooms.  To the south lies the remains of a colonnade and portico and, set back, a series of large barrel vaulted storage rooms which faced the sea. In these rooms, just as in the Roman port area of Herculaneum, dozens of skeletons were found of people waiting to be rescued by boat from the eruption of Vesuvius in AD79. In 2008 I was invited by John Clarke to join the team and started work on site at Villa ‘A’ helping with a small evaluation trench located in the southern area of the large swimming pool. One of its aims was to attempt to date the adjacent foundation wall of Room 78, the large diaeta (private room) to the south-west of the swimming pool. We excavated through demolition layers of Roman material which included fragments of exquisite fresco, painted stucco fragments and, the most wonderful of all, beautiful oil lamps with a variety of designs. To an archaeologist who normally excavates Roman sites in Britain the quality and quantity of finds was staggering. The Fourth Style fresco fragments indicated a terminus post quem date of about 45AD for the construction of the diaeta. The following year I returned to Oplontis with a small team from the Kent Archaeological Field School (KAFS) and a Landover full of archaeological kit. The drive from Kent, through France, across the Alps and down the spine of Italy was memorable and is something I still look forward to every year. In a way it is a drive through history, and gives one a feel of how extremes of landscape moulded the lives of past peoples. The 2009 season was busy and eight trenches were excavated at Villa ‘A’. In addition Giovanni Di Maio who had already undertaken some work on the geological formations below the villa cored three additional areas to the south of the villa and proved that Villa ‘A’ was situated on a cliff about 13 metres above the Roman sea level. Our work in 2009 included a test pit dug through the north-west corner of the pool. We found that the pool had originally been larger and had been reduced in width presumably to allow the colonnade of porticos on the west side to be built. In addition we excavated part of a circular fountain in Room 20. It had been revealed by workmen laying cables in 2007 and not recorded. On investigation we found a partly demolished fountain buried under a metre of demolition debris. The fountain had quite a pronounced tilt to it which might suggest Villa ‘A’ had been subjected to serious earthquake damage in the years before AD79. All the piping to the fountain had been robbed, and in addition a statue which graced the south edge of the fountain was no longer there, but its concrete ‘footprint’ was! Another of our trenches was located in the north-east corner of the north gardens and for once we were digging through layers of pumice deposited by the volcanic eruption of AD79. Underneath we found an open canal 80cm in width and finished in coating of cocciopesto (pink waterproof cement), known to archaeologists as opus signinum. The canal runs north with a slight curve to the east under the modern car park. The function of the aqueduct fed canal cannot be proved, but it is likely that it was an open water feature, part of an elaborate garden which went out of use in antiquity when it was backfilled with earth and debris.  Another garden we looked at was in Room 32, the peristyle in the servants quarters located to the east of the main atrium. We discovered evidence for an earlier peristyle that matched the footprint of the later build. The trench produced copious amounts of marble mosaic flooring, opus signinum slabs, and the exquisite marble nose from a small statue! The water features investigated in 2009 suggest that the first phase of the villa dated to about 50BC, and was seriously damaged in the earthquakes of AD62 with the water features decommissioned and either demolished or backfilled. In 2010 we excavated nine trenches with a view to unravelling the complexities of the water supply to the villa. In the south-east of the north gardens we excavated a large cistern with a capacity of about two cubic metres of water. It seems the cistern, constructed of opus signinum, was to prevent flooding in this part of the garden, to hold a water supply for the garden, and for use as a drain to the nearby portico that once lined the eastern side of the north garden and its adjacent room. The finds from the infill of the cistern were dazzling with large fragments of a Doric frieze constructed of super fine stucco, two types of antefixes, and part of a column constructed of wedge-shaped bricks and with stucco flutes. It was decided to excavate in the centre of the 60m swimming pool which required crowbars to remove the large basalt blocks which made up the substructure of the pool. Our daily water consumption went up from two litres a day in the shade to six litres! The reason for digging was that the ground penetrating radar had found a significant anomaly underneath the pool foundations. Unfortunately we did not find any anomaly but we did expose and record the two phases of pool construction, the eruption layers and the palaeosoils. Our attention then focused on the area immediately south of the pool. Four trenches were dug that exposed a portico at the south end of the pool, part of a wonderful marble floor of opus sectile, a room not recorded before with marble steps and a Doric column with stucco fluting still in situ (now Room 99). Found on these steps were copious amounts of pottery and a large piece of marble architrave with part of an acanthus scroll or volute. Our work at Villa A has gathered additional evidence that after the earthquake of AD62 large areas of the villa were badly damaged The finding of part of a column drum from the adjacent east wing in the cistern, the lifting of part of the opus sectile floor prior to the eruption of AD79, and the remodelling of the swimming pool suggest that major re-building work was being undertaken. The villa also had problems with its water supply which may suggest that the villa was not habitable at the time of the eruption in AD79. Villa B Initial GPR work had detected a series of anomalies that suggested the presence of earlier structures under the present exposed buildings.  In particular the investigation suggested that the complex lay just a few metres from the ancient shoreline. The wider settlement may have been a small town (Oplontis) or a commercial harbour serving the Pompeian countryside, and will be the first of its kind discovered in the Bay of Naples area. Work started in 2012 in the courtyard area with the aim of exposing the stratigraphy, and to examine the foundations of the building which may produce evidence of its function and chronology. We expanded the trench to the entire width of the courtyard and soon had to resort to crowbars as the original surface of the courtyard comprised large and occasionally very large basalt boulders with the gaps between boulders infilled with large sherds of amphorae. Some of these still retained residue which were bagged for analysis. Immediately under the basalt pavement was the first of many pyroclastic flows, the first dating to the Late Bronze Age. As we excavated down we exposed and recorded sequence after sequence of eruption strata and palaeosoils dating as far back as 1500-1600BC. Some of these surfaces had carted or sled ruts along with pottery sherds and remains of mud bricks. The lowest strata were littered with Bronze Age artefacts, and suggest there was a high level of Bronze Age activity in the environs of Oplontis B. Both ends of the trench gave an opportunity to investigate the foundation design of the colonnade which was unusual to say the least. A thick tufa stylobate sits on top of foundation blocks (sterobate) spaced to coincide with the joins between the blocks of the stylobate with the entire assemblage sitting on the same pyroclastic stratum which we found under the basalt paved courtyard. Sherds of Campania A Black Gloss pottery found in the foundation trench date the build of this colonnade to the 2nd century BC. The other trench we dug in 2012 was situated in the south-west corner of the peristyle. We needed to understand and record the interior foundations of the courtyard colonnade and have a look at the stratification. We quickly uncovered the original AD79 floor of beaten earth skimmed with cement. Underneath we found a capped water conduit built of opus incertum. On removing the capping stones the conduit was full of gray ash from the AD79 eruption, and under this layer another deposit of dried sludge which contained stamped Arretine sherds. In 2013 we returned to this area and expanded the trench to expose a complex water system with a settling tank plus two water channels and various drains. Of some importance is the fact that this complex water system cut through two previous floor levels which suggests the function of the building may have changed through time. Another team undertook the task of removing tons of modern debris in the area of the south portico. A thankless task undertaken in the glare of the Italian sun! But well rewarded by exposing layers of volcanic debris from the eruption of AD79. Underneath this layer we found the original floor surface with numerous Neronian and Flavian coins. Below that a complex of barrel vaulted drains was exposed which will need further investigation. Our final investigation was to examine part of the street north of the main complex. Originally excavated by the Italian team in the 1980’s, who discovered a street running east to west lined on both sides with simple town houses on both sides, it is apparent that these houses have ground floor rooms, some with the foundation step of a staircase leading to upstairs rooms, and some of which have a simple shrine dedicated to the household gods. Our investigation showed that some areas of the ground floor still retained debris from the AD79 eruption and had not been excavated. Underneath we found a simple beaten earth floor, the step for a staircase, a toilet and washing area and probably a kitchen area. The road outside the house was also excavated and showed it had two construction phases which may correspond to the two identified phases of the adjacent building, the first probably dating to the 2nd century BC when the building were probably used as workshops with a wide entrance, and the second phase when the entrance was narrowed and the building turned into domestic quarters. Indeed, three houses show walled up entrances, it now became a typical Roman street that included stone benches outside of each entrance. We will be back in Oplontis in June 2014 for another season of excavation and anyone can join our team. The only criteria is that you are a member of the Kent Archaeological Field School www.kafs.co.uk and that you have some experience or enthusiasm for Roman archaeology, Italian food and Italian sunshine! See also the website www.oplontisproject.org. Oplontis Project Oplontis Roman Villa B, Pompeii, Naples, in association with the University of Texas Week to be held in late May, early June 2015 Weekly fees: £175  Please note food, accommodation, insurance, and travel are not included. Flights to Naples are probably cheapest with EasyJet. To get to Pompeii take a bus from the Naples airport to the railway station and then the local train to Pompeii. Hotels are about 50eu for a room per night. We are staying at are the Motel Villa dei Misteri and the Hotel degli Amici. [email protected] [email protected] For camping (where I shall be) the site Camping Zeus is next to the hotel: [email protected] and is about 12eu a night. Transport to Oplontis from Pompeii can be provided. LAST COURSES IN 2014

Bones and Burials to be held on the weekend of October 4th & 5th. AUCTION NEWS

An extremely rare 2,000-year old coin, struck during the reign of Augustus, founder of the Roman Empire, is expected to fetch £350,000 at auction next month. The aureus coin was made between 27BC and 18BC and is in superb condition. It depicts Augustus as an ageless Apollo-like classical sculpture on one side, and the reverse features a heifer based on a long-lost masterpiece by a Greek sculptor.  A treasure hunter sheltering from a hailstorm stumbled on an old Saxon coin which has been sold for £78,000. The rare coin from the reign of Ethelberht II, king of East Anglia in the 8th century, was found in Eastbourne, Sussex. The "Out of the Ordinary" sale at Christie's South Kensington in September includes one lot that certainly appears to deserve the description, and indeed, if the speculation is justified, it must be one of the most extraordinary secular relics to survive from the Middle Ages.  Catalogued as "an extremely rare late medieval broadsword with an earlier Viking blade and bearing the arms of the Dc Bohun family, Earls of Hereford and Essex", it is possible that it was carried at three of the most memorable British battles: Stamford Bridge, Hastings and Bannockburn. The blade has a clear runic inscription, apparently identical to that on a Viking sword found in the bank of the River Derwent in Yorkshire close to the site where Harald Hardrada's Norwegian invaders were defeated by Harold of England at Stamford Bridge on September 25, 1066. Nineteen days later, Harold was killed at Battle in Sussex by William of Normandy. Many of his housecarls would have furnished themselves with the weapons of slaughtered Vikings before their remarkable forced march to the south coast. In turn, their bodies would have been scavenged by the eventual Norman victors. It is entirely plausible that such a blade could have had three owners in the space of one month in 1066. Humphrey De Bohun I, who may have been the Conqueror's Godfather, is identifiable in the Bayeux Tapestry by his beard — the only other Norman to sport facial hair was Eustace of Boulogne, who wore an "English" moustache — and is depicted eating greedily at Bishop Odo's table before the battle. If taken as a trophy, the blade was later remounted as a family sword, with the De Bohun arms on two shields on the pommel. There are touches of the original colours, and the blade was probably also decorated. Its original rounded end was reground to a point. In 1319 such a sword appears in the will of Humphrey De Bohun VII, 4th Earl of Hereford and Essex and Constable of England. Married to a daughter of Edward I, De Bohun was one of the great men of his day. However, he was out of favour with Edward II at the time of Bannockburn, the Scots victory fought 700 years ago on June 23-24, and so was replaced in command by the less competent Earl of Gloucester in that disaster for English arms. Although this sword was not by then a serious fighting weapon, it would have been a practical sidearm to wear in camp, and so may have seen its third battle even if not actually on the field. Indeed, it may also have been close at hand at a fourth battle eight years later when the 4th Earl met a particularly gruesome end. He was one of the rebel Lords Ordainers who fought Edward II at Boroughbridge in Yorkshire; while charging across a bridge on foot he was impaled by a spearman hidden below, and his agonised screams helped to stampede his followers. Coincidentally, a similar incident was said to have occurred at Stamford Bridge in 1066, just a few miles away. Although the sword's provable modern history goes back no more than 50 years, X-rays are consistent with the postulated dates and show no modern alterations or repairs. The sword is estimated to £120,000, and an accompanying medieval metal heraldic device with the De Bohun arms, which is thought to have been for display on a saddle pommel, is expected to make some £15,000. Huon Mallalieu is the author of 1066 and Rather More. BREAKING NEWS

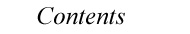

Archaeologists have uncovered one of the finest collections of Roman jewellery found in Britain, which was hastily buried as Queen Boadicea and her army advanced on Colchester.  Key to picture (above) 1 Coins in bag. 2 Silver bracelet. 3 Three gold armlets4 and 5. Some of the coins that fell out of the bag after it rotted. 6 Pair of gold earrings.7 Silver bracelet. 8 Four gold rings. 9 Pair of gold earrings. 10 Gold disc. 11 Silver armlet. WATCHING NOW Wendy Ide reviews Hercules 3D

Anyone looking for an account of the labours of Hercules is labouring under an misapprehension if they think that Brett Ratner's pumped-up popcorn flick has anything to do with ancient mythology. In fact, this swaggering tale of wise-cracking Athenian mercenaries has more in common with the creaky bluster of The Expendables than with the story of the mighty warrior who was the son of Zeus and his mortal lover, Alcmene. READING NOW

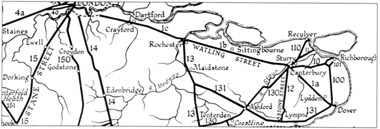

FOUR EMPERORS AND AN ARCHITECT: HOW ROBERT ADAM DISCOVERED THE TETRARCHY by Alicia Salter  It's the four tetrarchs, however, and particularly their founding member, the emperor Diocletian, that provided the seed for this generously informative book. At the end of the third century, Diocletian's solution to an increasingly unwieldy empire had been to share power with three co-emperors, each with his own region of authority and corresponding capital - none of which was Rome. (Raised in the Balkans, Diocletian visited Rome only once.) Each embarked on a suitably glorious architectural programme, Diocletian building himself a waterfront palace at Spalatro, modern-day Split in Croatia. Fast-forward to 1757, and we find a young Scotsman, Robert Adam, poring over its remains at the end of his Grand Tour. Alicia Salter sets herself a formidable challenge here, leaping back and forth between 14 centuries. But she manages it elegantly, enlisting the help of maps, plans and images, including beautiful reproductions of plates from the Ruins of Spalatro, which Adam published in 1764. She makes an excellent guide to his journey from Rome, where the budding architect set himself up in an apartment at the top of the Spanish Steps, via Venice (did he see the St Mark's tetrarchs?) to Diocletian's palace on the Dalmatian coast, where the Venetian authorities suspected him of espionage. Adam returned to London with a precious trunkful of drawings, soon to revive gleaming elements of Diocletian's retreat in some of the country's great houses - at Syon, Kedleston, Osterley, an Englishman's home was now his Roman palace. And often with the requisite eccentricities: the owner of Sal tram in Devon, we learn, took to hiding large sums of money around the house, so that an inventory after his death in 1768 reads: 'Cash in bags placed in the mahogany bookcase £3,717; ditto placed in the wainscot toilet £3,928.' As the final chapter of this book reveals, Adam overreached himself financially with his speculative Adelphi scheme. Demolished in the 1930s, this grand, Thames-side terrace of houses bore a strong resemblance to that ancient waterfront structure that so inspired the architect as a young man. Raised up on an arcade imitating the cryptoporticus at Spalatro, it was also the origin, argues Salter, of the very idea of terraced housing in London. Who knew we had Diocletian to thank for that? Sophie Barling LAUGHTER IN ANCIENT ROME by Mary Beard 'Oink, oink,” says the English and American pig. But Welsh pigs are thought to grunt “soch, soch, soch”, while the Hungarian goes “uí, uí”. Pig-song – or our rendering of it – varies from place to place. The same cannot be said of laughter. Almost universally, humans have transcribed their laughter as “ha ha”, “tee hee” or something very close. “Hahahae”, for instance, cries the sycophantic slave in Terence’s The Eunuch – a Roman comedy already old when Cicero was young. Yet the pleasingly timeless “look” of laughter might be the lone straightforward point one can make on the subject, as Mary Beard’s superbly acute and unashamedly complex study of Roman laughter proves. For laughter is a funny old thing: as contested in antiquity as it is by modern theorists. How can laughter be a rational response to tickling? Are we the only “laughing animal”, as Aristotle once said? Or, as he may have claimed elsewhere, can herons do it too?  Among humans (and possibly herons), laughter is only universal up to a point. It travels badly across time and space: it’s hard to share a joke across the Channel or to find much to laugh at in a yellowed copy of Punch. But they do say “the old ones are the best” – and some, at least, may not be so bad. In the late-Roman joke book Philogelos (The Laughter Lover), Beard exhumes some passable sketches about the dim-witted Abderites – like the Irish, a recurrent butt – along with that classic barbershop retort, recycled by Enoch Powell: “ 'How would you like your hair cut, sir?’ 'In silence.’ ” As Beard is perfectly aware, these antique jokes are made no funnier by scholarly exegesis (like a frog, jokes die on dissection). However, she sets about them with her scalpel merrily enough and, by interrogating the moments in extant Roman-era literature where laughter is depicted, Beard constructs a richer portrait of Roman thought than the one we had before. The Romans liked to think about power, for instance, as a question of who was laughing at whom. When the mad emperor Commodus, masquerading as a gladiator on the Colosseum’s sands, brandished a severed ostrich head at the senators in the crowd, none of them could check their laughter. One, Cassius Dio, records that only by chewing on laurel leaves plucked from their garlands could they hide their mirth. Commodus meant to intimidate his aristocracy, but their amusement gave him a subtle dressing down – laughter used “like a bomb”, as Wyndham Lewis would put it in 1914.  Violence in some degree seasoned many occasions for Roman laughter, of which the most grotesque must be the martyrdom of St Lawrence. Perishing slowly on a red-hot griddle, the urbane saint overcame his pain to request that he be turned over; his lower flank, he announced, was now perfectly cooked. The Roman vocabulary of humour, while copious, was surprisingly uneven. Despite myriad words for “joke” and “wit”, there is no Latin word for “smile”. Their solution was to use subridere (whence the French sourir): literally, “a suppressed laugh”. This paucity, Beard suggests, indicates the smile’s minor role in Roman social niceties – bolstering, perhaps, a theory that the smile, as we understand it, was an invention of the Middle Ages. Beard’s eye for textual minutiae is one of her book’s great strengths. Yet, although her mode is switched firmly from “television” to “don”, Beard’s text speaks lucidly to the non-expert, who will find pomposity entirely absent and jargon pared back to a minimum. Laughter in Ancient Rome might seem lean on satisfying conclusions. Yet Beard began it with only two pledges: to make the study of laughter messier rather than tidier; and that, despite wending further into unknowables and uncertainties, her road would have been worth travelling. Both promises are kept. To our vision of the solemn grandeur that was Rome, she restores a raucous, ghostly laughter. Why Hobbits triumphed in the Great War  Despite the slaughter in the trenches, JRR Tolkein and CS Lewis saw heroism and nobility in the war to end all wars. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle called it "the most terrible August in the history of the world". He was lamenting the opening weeks of the Great War: the conflict that inaugurated the mechanised slaughter of human beings on an scale never seen before. Before it was over, nearly ten million soldiers perished in a storm of bombs, smoke and steel. Lost along with them were the cherished assumptions of a generation: the European belief in progress, democracy, morality and religion. The watchword of the post war years was disillusionment. "1 think we are in rats' alley," wrote TS Eliot, "where the dead men lost their bones." Erich Maria Remarque, in his classic war memoir All Quiet on the Western Front, predicted a generation "broken, burnt out, rootless and without hope". Yet two extraordinary authors and friends — both soldiers in the First World War — rebelled against this prevailing mood. Rejecting the agnosticism and cynicism of their era, JRR Tolkien (a Catholic) and CS Lewis (an Anglican) insisted upon a moral universe: evil was a force that threatened every human soul but God and goodness were the ultimate realities. Though often dismissed as escapism, Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings and Lewis's The Chronicles of Narnia present a vigorous defence of the heroic tradition: a vision of human life tempered by the experience of war, yet nourished by a Christian sensibility. The worlds of Middle-earth and Narnia, after all, share a view of the world that is both tragic and hopeful. The tragedy lies in the corruption caused by the desire for power, often disguised by appeals to religion and morals. Virtually no character in their stories is immune to the temptation. In Lewis's Prince Caspian, Nikabrik, initially a foot soldier in the fight for Narnia, turns traitor when Asian, the great lion, fails to come to their aid. Nikabrik makes the appalling suggestion that his comrades enlist the help of the White Witch. "We want power," he says, "and we want a power that will be on our side." In Tolkien's trilogy, we learn that Saruman, a wizard originally committed to helping Middle-earth in the struggle against Mordor, has fallen under the sway of the Ring of Power. Prudence, he argues, demands a temporary compromise with Sauron the Dark Lord. "We can bide our time, we can keep our thoughts in our hearts, deploring maybe evils done by the way," he says, "but approving the high and ultimate purpose." No work of fiction better describes the Great War and its aftermath. Despite an appeal to lofty moral principles, none of the combatant nations resisted using the most horrific weapons ins agalnsl the enem) mortars, machine guns, tanks, poison gas, starvation. "When it was all over, torture and cannibalism were the only two expedients that the civilised, scientific, Christian states had been able to deny themselves," wrote Winston Churchill, "and these were of doubtful utility." The result was that the shell shocked veteran became a walking metaphor for much of postwar Europe. Meanwhile, all manner of Utopian schemes — eugenics, communism, fascism — were welcomed into the most educated circles in the 1920s. "A profound sense of spiritual crisis," writes the historian Modris Eksteins, "was the hallmark of the decade." Tolkien and Lewis, two of the most influential Christian authors of the last century, set out to confront this moral and spiritual crisis. The Iwo had met as young dons at Oxford in 1926, discovered a mutual love of mythology, and established a friendship that shaped their literary careers. Though they could never glamorise combat — both lost their closest friends in the war — they chose to remember not only its horrors and sorrows but also the courage, sacrifice and friendships that made it endurable. "My Sam Gamgee is indeed a reflection of the English soldier," Tolkien said, "of the privates and batmen I knew in the 1914 war." Together they sought to retrieve the epic romantic tradition, embodied in works such as Beowulf and Le Morte D'Arthur, and to make it attractive to the modern mind. The Life was tempered by war but nourished by God and goodness heroes of Narnia and Middle-earth do not shrink from the sight of hacked-off limbs and smashed skulls. But they are warriors — men, women, hobbits, dwarves, horses and even mice — of great humility. Conscious of their frailties, they nevertheless are determined to play their part in the war against evil. "We know a good deal about the Ring," Merry tells Frodo. "We are horribly afraid — but we are coming with you; or following you like hounds." Escapist fantasy? "It offers the only possible escape," wrote Lewis, "from a world divided between wolves who do not understand, and sheep who cannot defend, the things which make life desirable." It requires no imagination to see that the ‘real world’ in which we find ourselves is being ravaged by a new and fanatical breed of wolves. The heroic ideal may be the only thing that stands in their way. Joseph Loconte, associate professor of history at the King’s College, New York. MUST SEE Celebrating Sutton Hoo 75 years on  The new gallery gives an overview of the whole period, ranging across Europe and beyond - from the Atlantic Ocean to the Black Sea, from North Africa to Scandinavia. It is the unique chronological and geographical breadth of the British Museum's Early Medieval collections that makes such an approach possible. As well as giving the Sutton Hoo ship burial's treasures greater prominence within the museum, the new display will also act as a gateway into the diverse cultures featured in the rest of the gallery, in chronological, geographical and cultural zones. These include the Late Roman and Byzantine Empires, Celtic Britain and Ireland, migrating Germanic peoples, Northern and Eastern Europe, the Anglo- Saxons and the Vikings. Among the outstanding treasures on display will be the Lycurgus Cup, the Projecta Casket, the Kells Crozier, the Domagnano Treasure, the Cuerdale Hoard and the Fuller Brooch. The design, object selection and interpretation aims to develop a more coherent narrative and to display star objects more effectively than ever before - this includes extraordinary objects from a period that was anything but the 'Dark Ages'. The new display will also feature artefacts never shown before - including Late Roman mosaics, a huge copper alloy necklace from the Baltic Sea region, and a gilded mount discovered by X-ray in a lump of organic material from a Viking woman's grave, over a century after it was acquired. Despite so many different peoples spread across vast distances over a long period, the key themes running through the gallery's narrative will put the objects on display in context, highlighting how diverse parts of the collections relate to one another. Lindsay Fulcher  STUDY DAY A day in Bath followed by a Twilight Tour & Dinner in the Roman Baths. KAFS Visit on Saturday 13th December at 9.30am with Stephen Clews Curator of the Roman Baths. 9.30 Introductory talk by Stephen Clews 10.45 Visit to the Pump Room for spa water 11.15 Visit the Roman Baths site, including special access to underground passages not open to the public. 12.30-1.30 Lunch break 1.30 Tour of old spa buildings and Bath's Georgian upper town 4.30 Meet your evening guide at the Great Bath for an exclusive guided tour around the torch lit baths followed by a three course dinner at the Roman Baths Kitchen. A day in the beautiful Cotswolds and the graceful city of Bath will reveal the Roman heritage of the area. Our tour leader will be Stephen Clews, Curator of The Roman Baths for the last 16 years, and prior to that Assistant Curator at the Corinium Museum in Cirencester. The study day begins with an introductory talk by Stephen Clews followed by a gulp of spring water in the Great Pump Room at Bath. Then we visit the Roman Baths and Temple complex built around the hot springs of Bath, which became a place of pilgrimage in the Roman period. This tour will include special access to underground passages and the spa water borehole. The spa theme will continue as we trace the story of seven thousand years of human activity around the hot springs, which has created this World Heritage city. The afternoon will conclude with a walk around the Georgian upper town. In the early evening we meet up at the Roman Baths for a torch lit guided tour of the Roman Bath Museum followed by Dinner at the Roman Baths Kitchen opposite the entrance to the Roman Baths. To join the ‘behind the scenes’ visit with KAFS on Saturday 13th December 2014 email your booking to [email protected] Places available for five members only at £75 per person. FIELD TRIPS Join KAFS on a field trip to Zeugma now re-scheduled to May 15th, 16th, 17th. 2015. It is a not a trip for the light-hearted but there are direct flights by Turkish Airlines direct to Gaziantep from Gatwick at about £250 return. Local accommodation and a local mini-bus plus local guide will be available and Dr Paul Wilkinson will be your guide. We have six places left, mini-bus and museum costs to be shared amongst members. For more details email Paul Wilkinson [email protected]  The ancient city of Zeugma was originally founded as a Greek settlement by Seleucus I Nicator, one of the generals of Alexander, in 300 BC. King Seleucus almost certainly named the city Seleucia after himself; whether this city is, or can be, the city known as Seleucia on the Euphrates.  In 64 BC Zeugma was conquered and ruled by the Roman Empire and with this shift the name of the city was changed into Zeugma, meaning "bridge-passage" or "bridge of boats". During Roman rule, the city became one of the attractions in the region, due to its commercial potential originating from its geo-strategic location because the city was on the Silk Road connecting Antioch to China with a quay or pontoon bridge across the river Euphrates which was the border with the Persian Empire until the late 2nd century. Museums we will visit include: • Archaeological Museum This local archaeological museum hosts some stunning mosaics excavated from the nearby Roman site of Zeugma. The museum, which also has a small cafe inside, is wheelchair accessible. • The Castle's Museum. It is a great opportunity to learn from the Turkish point of view what happened in the WWI, especially what concerns to the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire and the further occupation. The view from the top of the castle is amazing. • Kitchen Museum. Museum about Turkish traditional cuisine, food, ingredients, tools and bon tòn. Very interesting. • Zeugma Mosaic Museum. Zeugma Mosaic Museum, in the town of Gaziantep, Turkey, is the biggest mosaic museum on the world, containing 1700m2 of mosaics. For more information on Zeugma see: www.zeugmaweb.com/zeugma/english/engindex.htm QUIZ The first reader to identify this crop mark and its location wins a free weekend of their choice at the Kent Archaeological Field School. Send your answers to [email protected]  SHORT STORY "If history were taught in the form of stories, it would never be forgotten" Rudyard Kipling Faction articles of life in Roman Kent by Paul Wilkinson have been published monthly in the county newspaper of Kent and are a hit with readers. For the amusement of academics read on!On March 29th 2013 I was working with my team of archaeologists on the site of Durolevum, the ancient Roman small town of which Faversham is its successor. I was troweling away in the entrance to a small shop owned by a Roman shopkeeper called Celsus. I looked at my watch and it said 10am- time for a tea break. One of my colleagues said I was too late the clocks went back last night and it’s now 11am! I groaned, closed my eyes and when I opened them these he was again, Celsus leaning on his counter and smiling. ‘What an odd way to keep the time, you follow the Roman months, why not follow our time as well?  I asked him how it worked, and he said ‘well your hours each comprise a uniform sixty minutes of sixty seconds each, but for Roman time the twelve hours of the day are divided by the gnomon between the rising and the setting of the sun, while the hours of the night were conversely divided between sunset and sunrise; in proportion as the day hours were longer at one season, the night hours were, of course, shorter, and vice versa. The day hours and night hours were equal only twice a year: at the vernal and autumnal equinoxes. They lengthened and shortened in inverse ratio till the summer and winter solstices, when the discrepancy between them reached its maximum. At the winter solstice (December 22), when the day had only 8 hours, 54 minutes of sunlight against a night of 15 hours, 6 minutes, the day hour shrank to 44 minutes while in compensation the night hour lengthened to 1 hour, 15 minutes. At the summer solstice the position was exactly reversed; the night hour shrank to its minimum while the day hour reached its maximum, does that make sense?’ I was confused and asked him what a gnomon was? ‘Well let’s ask the road surveyor who is working outside. Graecus was a Roman land surveyor, a civilian Agrimensores highly trained in the precise skills of geometry and measurement. Graecus explained his job: ‘Land is usually set out on a square grid, tied into Roman roads. Roads would provide a geographic reference to land and estate division, with a plot being located by referring to a specific milestone along a particular road together with the required distance, left or right. ‘We use variety of surveying instruments, including the groma, a device for establishing a survey line which is a continuation of, or is at right angles to, an existing line. The dioptra was used for measuring horizontal angles, for plan surveying, vertical angles and for levelling, and the portable sundial, the gnomon, could be used to find true north and south’. He tells us that in order to find north, describe a circle into the ground and push a stick (the gnomon) vertically into the centre. The stick's height must be such that the end of its shadow in the early morning and late afternoon lies outside the circumference of the circle, but inside at midday. Once in the morning and again in the afternoon, the end of the shadow will just touch the circumference. Graecus tells us to join these points thus obtaining a chord. Then, draw a line from the centre of the circle which bisects this chord, and this line is true north.  Note the time from an hour glass and rotate the sundial until the shadow of the gnomon coincides with the corresponding time on the circumference of the brass circle. The gnomon is now back to true north and the instrument has been used not as a sundial, but as a sun-compass. The instrument is now lined up exactly with true north. The other method we use is the right-angled traverse lines of known length. The distance and angle of the proposed route can then be worked out. When obstacles such as rivers occur, the triangulation method of survey may be used. The traverse lines can be permanently established in the landscape with stone markers, which could also be used for plot survey and division. To measure the distance between way-points, a hodometer, as described by my colleague Vitruvius, is used. It consists of a wheel which turned cogs to record rotations, and so indicated the distance travelled. However, even if such an instrument was not available, Roman army soldiers were trained to march at a steady rate of 1,000 paces to a Roman mile, and these ancient armies had a bematistae whose job it was to record exactly the daily distance covered by a legion’. I thanked them both and looked at my watch inscribed with Roman numerals, and when I looked up they were both gone leaving me with the task of recording one of the great roads of the Roman Empire which started in Britain at Richborough and is now called Watling Street. Paul Wilkinson KAFS BOOKING FORM You can download the KAFS booking form for all of our forthcoming courses directly from our website, or by clicking here KAFS MEMBERSHIP FORM You can download the KAFS membership form directly from our website, or by clicking here |

||||||||

If you would like to be removed from the KAFS mailing list please do so by |

|||||||||